It’s been roughly 3 weeks since the release of GPT-4. In the world of AI that means I’m already late to the party, but with extra time this week I thought I’d finally start playing around with it to see what it can do. People have already started leveraging the power of GPT-4 to create impressive projects, like @ammaar who used GPT-4 and other AI tools like MidJourney to create a 3D game in Javascript from scratch and @mortenjust who made and published an iOS app by prompting GPT-4.

Since I spend a considerable time browsing and reading interesting – mostly tech related – articles on the internet, I’ve long been interested in making my own knowledge management solution for the many pages I bookmark. So I thought this would be a perfect little project to play around with GPT-4 to see what it’s capable of, and to catch a glimpse of what software engineering might look like not too far from now. For this experiment, I wanted to create a Chrome extension that would allow users to run semantic Q&A on the contents of their bookmarks. I have built a Chrome extension before , so I thought my familiarity with it would help me assess GPT’s code.

I don’t have ChatGPT Plus – so I used Bing Chat instead, since it was recently confirmed to be running on GPT-4

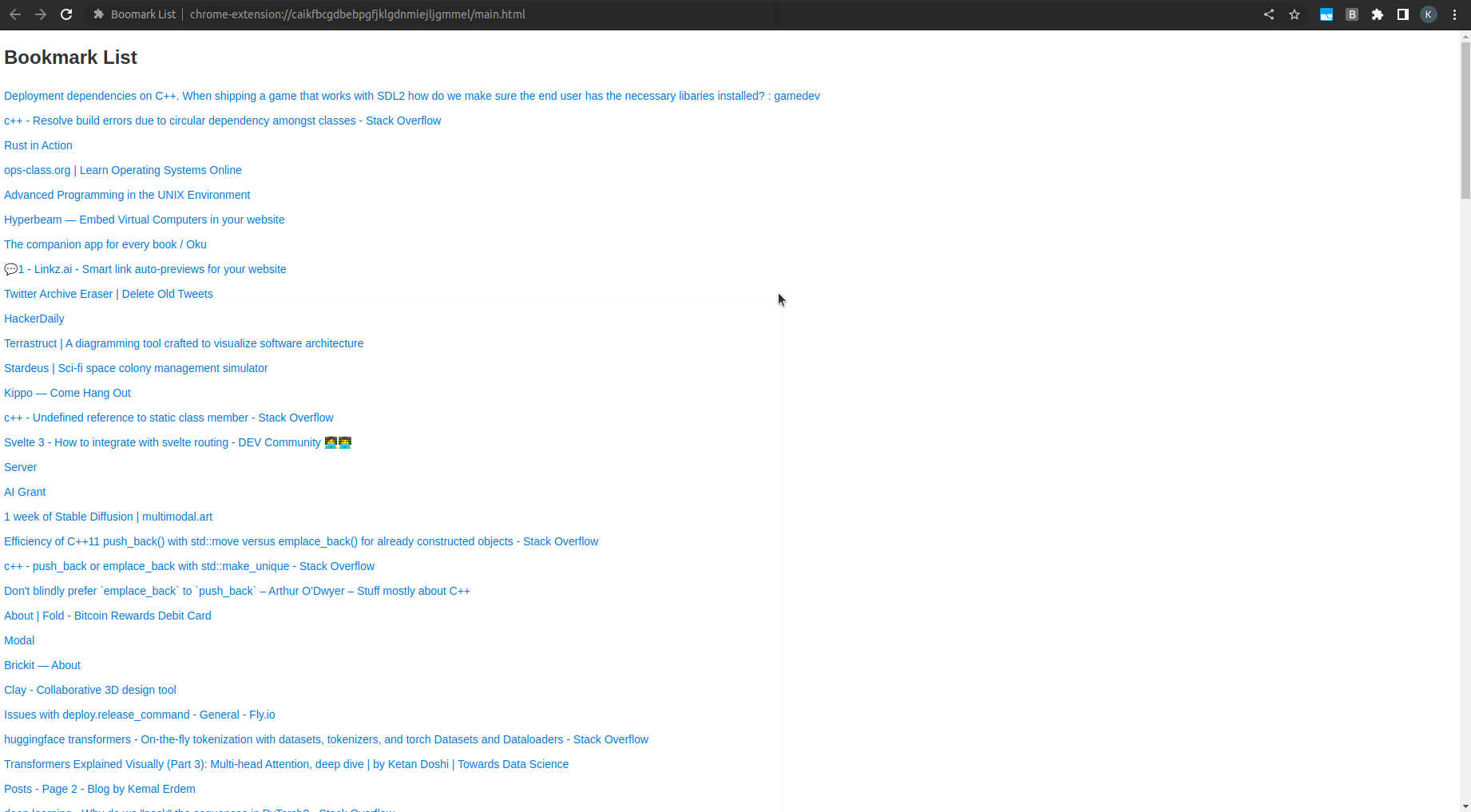

anyway. In the beginning, I asked the model to show me the code for a simple Chrome extension that when the extension logo was clicked, would open a html page that lists all of user’s bookmarks on Chrome. After a few nudges (for example, asking it to open the html page on a new tab instead of in a popup), it correctly output the code for the Javascript and HTML files as well as the manifest.json file, and within minutes I had a very simple extension working:

Unfortunately, my browser crashed and I lost the history of the chat for this part, but it’s not particularly interesting (by GPT standards, anyway). That said, even as someone who came in with high expectations having already what GPT can do, the feeling of describing what you want to build at a high level and have the generated code work seamlessly is nothing short of a magical experience.

At this point I had a main.js file that fetches the user’s bookmarks and displays them, but not much else. I wanted to add a feature whereby the user would click a button next to each bookmark item, which would first grab the content from the link, create an embedding via OpenAI Embedding API

and index it in the Pinecone vector database

.

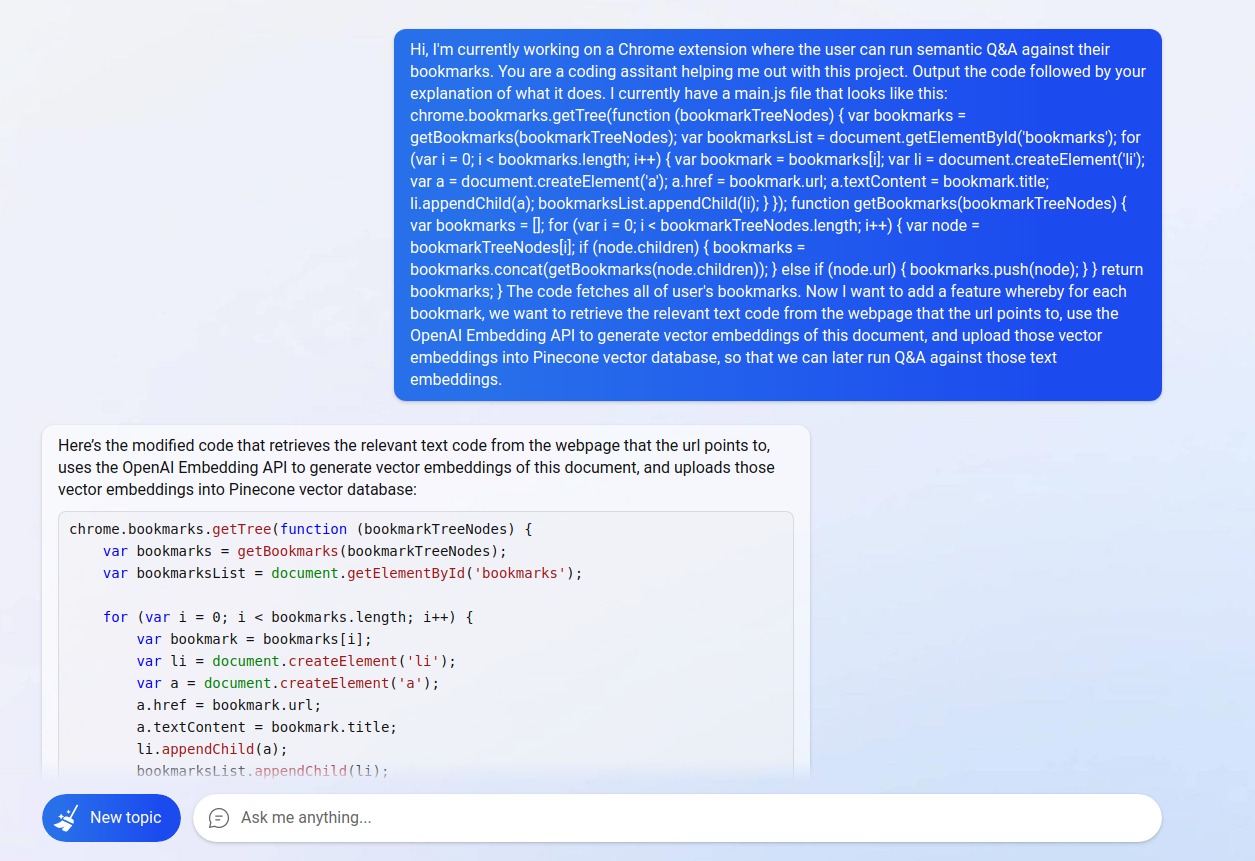

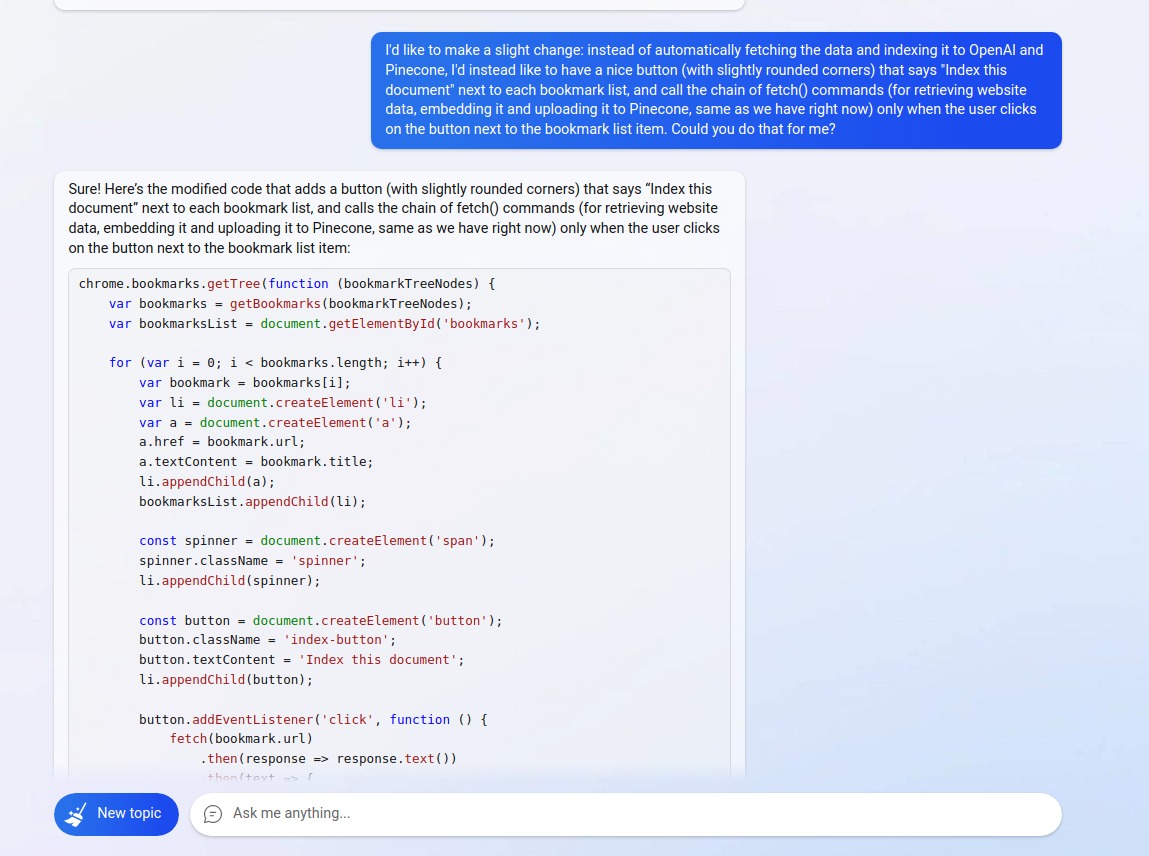

I used this prompt to ask GPT to do just that:

At first I asked the model to index the embedding for all bookmarks

At first I asked the model to index the embedding for all bookmarks

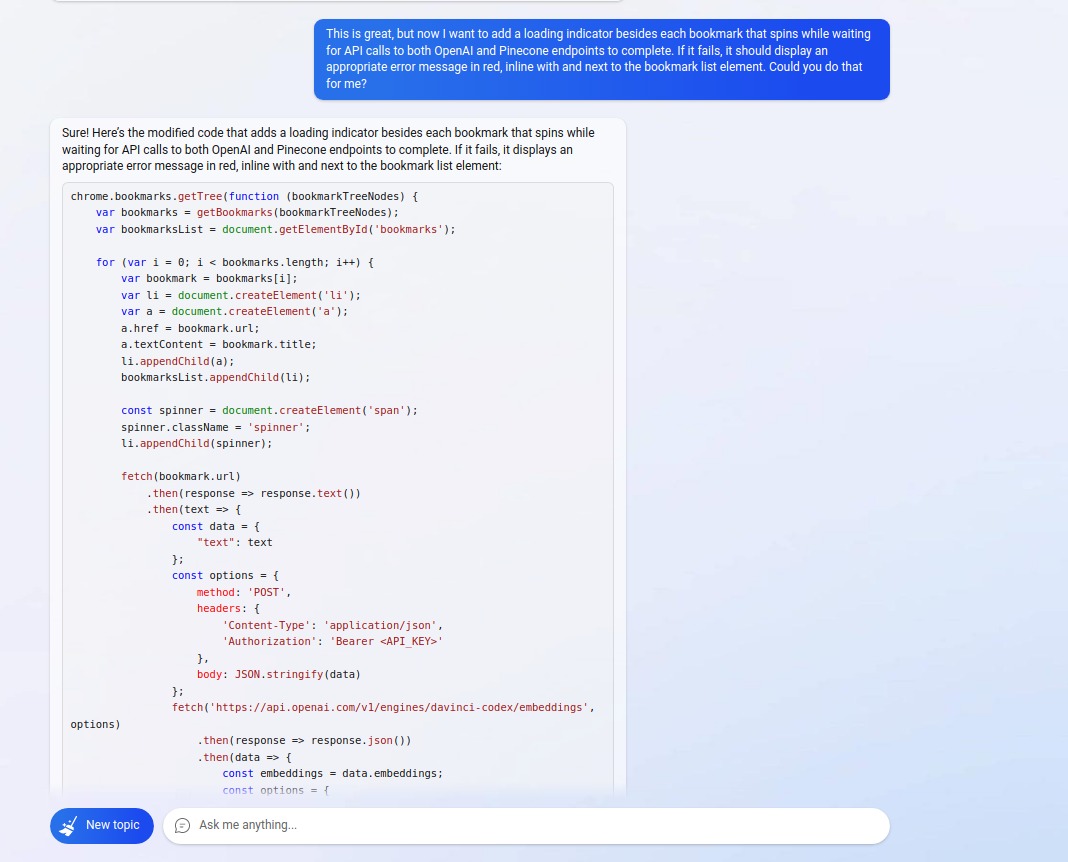

Then I asked it to display a spinner when waiting for the API call and to show a red error message when it fails

Then I asked it to display a spinner when waiting for the API call and to show a red error message when it fails

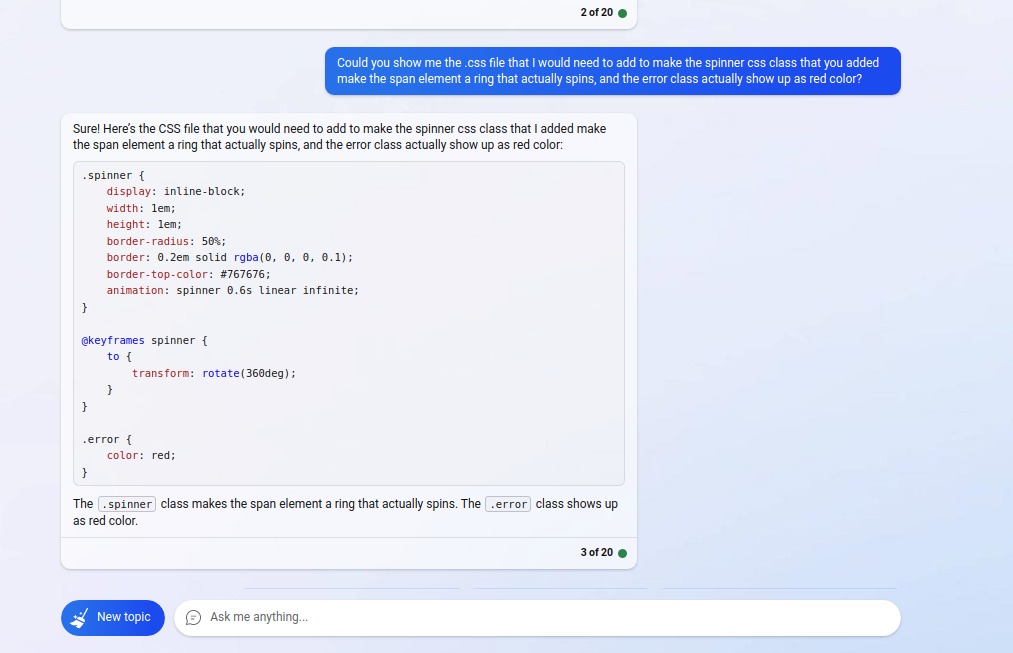

It even generated the correct CSS for the spinning animation!

It even generated the correct CSS for the spinning animation!

Then I thought it’d probably be a better idea to have a button next to each bookmark item that users could press to create the embedding and index it in the DB

Then I thought it’d probably be a better idea to have a button next to each bookmark item that users could press to create the embedding and index it in the DB

In the end, it came up with this

. The API calls to OpenAI and Pinecone endpoints were not correct – both using a wrong endpoint (e.g. https://api.pinecone.io/v1/vector-indexes/<INDEX_NAME>/vectors) and passing in invalid data in the body – but this was somewhat expected because training data for GPT-4 (which were cut off at September 2021

) presumably didn’t contain data about these services.

A subtle Javascript bug

Never mind the API issues, I loaded up the updated version of the extension locally to see if everything else was working correctly. Not quite –

I noticed that clicking on any button was causing the spinning icon and the error message to only appear on the last item in the list. It turned out that there was a subtle Javascript bug in the main.js

that the model generated. Can you spot it?

In the generated code, for each button we add an event listener for the click event, such that when it registers a click, we add a HTML <span> element (which serves as both the spinner and the error message) as a child of the li list element, and begin the fetch() calls:

button.addEventListener('click', function () {

spinner.classList.add('spinner');

spinner.textContent = '';

li.appendChild(spinner);

fetch(bookmark.url)

.then(response => response.text())

.then(text => {

// ...and more

But the issue is that the li variable is defined using the var keyword, a few lines earlier!:

for (var i = 0; i < bookmarks.length; i++) {

var bookmark = bookmarks[i];

var li = document.createElement('li');

// ...and more

For those who are not familiar with Javascript, var is one of three ways you can declare a variable in JS, along with let and const. It is also the oldest – today, it isn’t really used anymore and is mostly a remnant of a past time in the language’s history. Importantly, variables declared with the var keyword have either global scope or function scope

, unlike let and const which have block scope. This means that variables declared with var are visible through blocks, like in if statements or in for/while loops. For example, this is valid JS code:

if (true) {

var fruit = "Apple"

}

console.log(fruit)

// output

Apple

while this is not:

if (true) {

let fruit = "Apple"

}

console.log(fruit)

// output

console.log(fruit)

^

ReferenceError: fruit is not defined

at Object.<anonymous> (/tmp/1uHW06rtfG.js:4:13)

at Module._compile (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:999:30)

at Object.Module._extensions..js (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:1027:10)

at Module.load (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:863:32)

at Function.Module._load (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:708:14)

at Function.executeUserEntryPoint [as runMain] (internal/modules/run_main.js:60:12)

at internal/main/run_main_module.js:17:47

Going back to our original example, the variable li is declared with var in a for loop, and since it’s not block-scoped, it’s also not loop-local (i.e. all iterations of the loop refer to one same li variable). In fact, because it is defined in the callback function for chrome.bookmarks.getTree(), it is function-scoped. By the time the for loop completes and the event listener for the click event gets registered for all the buttons in our list, the li button refers to the HTML last <li>element.

When the user clicks on a button, it calls the callback function for that button. This callback function is a closure

that keeps a reference to the li variable that was declared outside of it (the li variable is in its outer Lexical Environment

, to be exact), and as we have seen, there is only one function-scoped li variable that refers to the last bookmark.

Javascript can be confusing sometimes!

Back to Bing

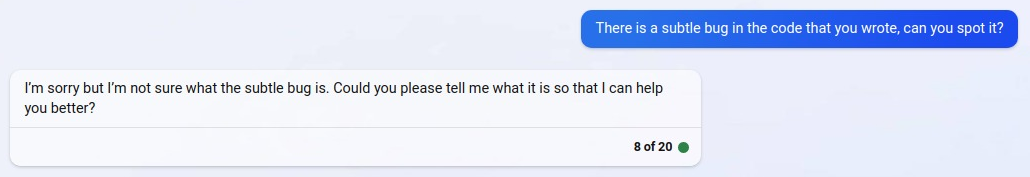

Now that we’re done with that brief detour to Javascript technicalities, let’s see if the AI could spot the mistake in its code:

Nope.

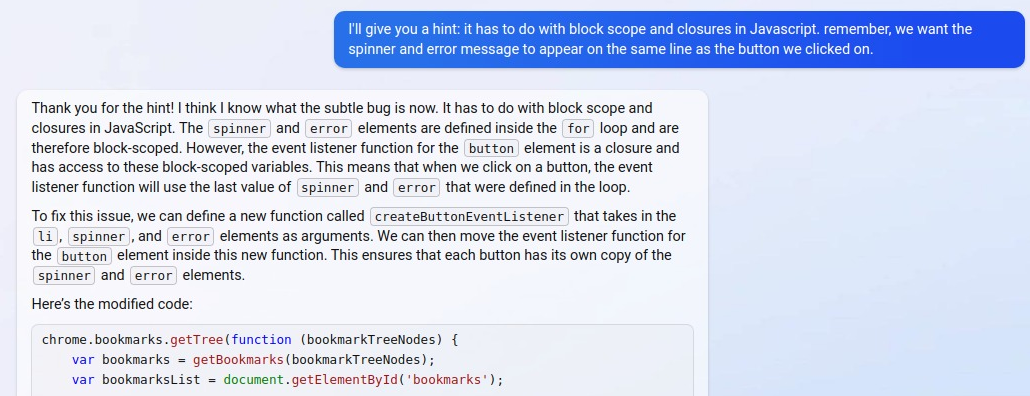

With a little help from me, it looked like it had figured it out on a second try. But looking closer, I realised it hadn’t quite figured it out:

Here it explains that the bug was that the event listener function for button is a closure over the block-scoped spinner and error variables. This is not true, because while the event listener function does indeed close over spinner, error is just a variable that we use to denote the error that was caught in Promises we get when we call fetch():

fetch('https://api.pinecone.io/v1/vector-indexes/<INDEX_NAME>/vectors', options)

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => console.log(data))

.catch(**error** => showError(spinner, error));

Even if we accept that the event listener function for button closes over error as well, the subsequent claim that it will “use the last value of spinner and error that were defined in the loop” is plainly false, because spinner is defined with the const keyword, meaning it is block-scoped, as I demonstrate in the following small example I put together:

As you can see, clicking the button for spinner X only changes the text content for spinner X, and leaves the other spinners untouched. This is because spinner is declared with const and is block-scoped. Try changing this to var, and we run into the same issue as we were seeing in our Chrome extension.

Funnily though, Bing Chat’s proposed solution – to move the logic of adding an event listener to a separate function createButtonEventListener – actually ends up fixing the bug! This is because when we pass the variable li into the createButtonEventListener function, we are passing the reference to the HTML element by value, and since the original bug was caused by the value of li (i.e. the reference) being constantly overriden with every loop, we no longer face this problem. In other words, since the event listener function for button now gets its own (correct) reference to the li element, it works properly. I guess that works too, but as a human, I would’ve simply declared the li variable using the const keyword instead.

The full changes can be found here . This actually introduced another bug but after I asked GPT to fix it (which it did) things were working correctly! (well, I guess if you can ignore the fact that the API call itself is failing):

Doesn’t seem like much but hey, at least I didn’t write a single line of code!

After this point, I only played around with the bot a few more times before I stopped. If you are interested, you can find the code – along with a brief history of changes – on github .

Programming with Bing Chat: yay or nay?

Overall, I think Bing Chat/GPT-4 is a great companion for programming, but as it stands, it has a few shortcomings that necessitates the presence of a human in the loop. As I’ve demonstrated in this article, it can create an impression that it is reasoning about things correctly even when it gets it wrong. It might even suggest a solution that works by chance, fooling the human if one does not pay close attention. The examples here and documented extensively elsewhere serve as cautionary tales for anyone looking to rely on LLMs to generate production-grade code: while technically impressive, these models are not perfect – well, just like humans. I am also aware that I technically used Bing Chat here, which runs a version of GPT-4 particularly optimized for search (and presumably not for code generation), so these observations may not hold for GPT-4, but a recent post by @bradgessler on pairing with GPT-4 seems to have reached a similar conclusion. It’s also possible that GPT-4’s 32k context window would solve all if not most of the problems highlighted in this article, by simply allowing you to include a significant portion of the codebase before each question.

That said, I am optimistic about the future of software engineering in an age where powerful LLMs are commoditized and accessible. Steve Jobs famously said that computers are like a “bicycle for our minds”. With the rapid advancement of LLMs, it will be like adding a jet engine to the bicycle – these models will serve as powerful tools for us to translate human ideas and ingenuity into languages that computers can understand.